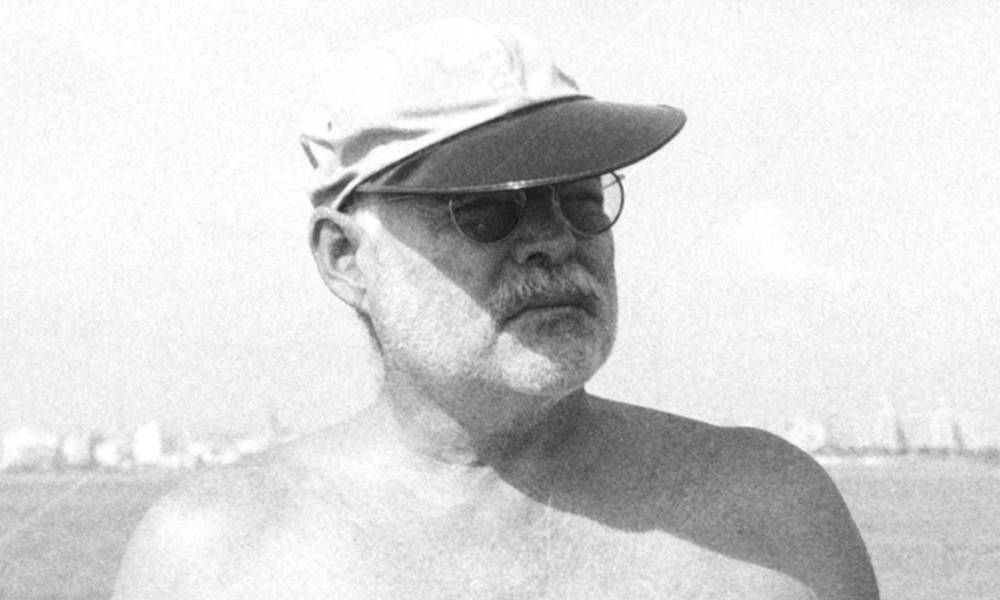

When one thinks of Ernest Hemingway, it’s hard to not think that, in some ways, the world will never have another man like him. A sensitive outdoorsman with a cosmopolitan (though often pessimistic) worldview, Hemingway was able to slide seamlessly through cafe life in Paris, the trenches of Italian war zones, and the sleepy wilderness of Idaho. It’s not just Hemingway’s writing that has canonized him as an American icon. His persona has cemented him as a role model for men in everything from lifestyle choices, to outdoorsmanship, to the menswear space.

And to understand Hemingway the writer, one must first know Hemingway the man.

Born in Illinois, Lost in France

In 1899, Ernest Miller Hemingway was born to an upper-middle-class family in the suburbs of Chicago. His mother a musician, his father a physician, Ernest had a comfortable upbringing that anyone would describe as all-American. In high school, he played a number of sports and was recognized for his innate sportsmanship that would be a running theme throughout his life. Academically speaking, to no surprise, he excelled in English and was part of the school’s orchestra.

Hemingway’s signature style of writing first began to develop in these early years, where he imitated the curt, matter-of-fact language of sports writers of the time. He applied this style to his years as editor for the school newspaper and yearbook.

At 18, Hemingway joined the American war efforts on the Italian front by joining the Red Cross (he had been rejected from the Army due to his poor eyesight). While in battle, he was seriously wounded by mortar fire, which ultimately led to his return to Illinois a changed man. Not yet 20, his time in a warzone had a lasting effect on his outlook on life and his own mortality, as it does for many who see combat. He would continue to incorporate these themes into his writing for the rest of his life.

By 1923, Ernest and his first wife, Hadley, were living in Paris with Hemingway working as a foreign correspondent (back then, a reporter could make a good living in Paris). By all accounts, this was when life really began for Hemingway. He met Gertrude Stein, and through her he became incorporated into the fold of the Lost Generation — a tenuously-associated group of intellectuals and artists who lived in Paris during the early 20th century. Here, Hemingway was introduced to (and influenced by) such characters as Picasso, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and more.

It was also during this time that Hemingway began to forge a career away from newspapers and into books. During the Paris years, he published some of his most well-known works, including: In Our Time, The Sun Also Rises, and the beginning of A Farewell to Arms were all finished in Paris. By 1928, he and his new wife, Pauline, were ready to move back to the United States and they settled in Key West, Florida.

By this point, Hemingway was no longer the Paris-living bohemian, but a full-fledged writer with prestige, responsibilities, and a growing interest in the outdoors. He split his time between Wyoming in the summer and Key West in the winter, describing the Wyoming landscape as a paradise. The rugged version of Hemingway (big beard, big sweaters, big muscles) was beginning to make its appearance here.

The world turmoil of the 1930s and 40s meant that Hemingway was once again back in the war zone as an onlooker. He took assignments covering the Spanish Civil War and the Normandy Landing during World War II.

After the War, he took up residence in Cuba and found a new wife along the way. He also continued to put out classics like The Old Man and the Sea, which won the Pulitzer Prize (subsequently earned the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954).

In 1960, Hemingway and his wife left Cuba forever after Fidel Castro threatened to nationalize all property owned by American residents. They set up a new life in Idaho. Hemingway’s mental and physical health began to deteriorate: he suffered paranoia, drank excessively, worried about taxes and the property left behind in Cuba, and went through successive depressive episodes which eventually led to 15 electroshock therapy procedures.

Ultimately, on July 2, 1961, Ernest Hemingway committed suicide with a shotgun. He was 61 and was survived by four wives, three children, and six bestsellers.

Getting the Papa Look

Hemingway is most famous for his writing that relies on simple language as truth and personal experience as the storyboard. A Hemingway sentence is easily identifiable for its brevity, its lack of adjectives and description, and its forward-motion storytelling that was more photographic than prosaic.

But another side of the man that has lived on past his death is his influence on the outdoor lifestyle. While it’s nearly impossible to replicate the beauty of Hemingway’s prose (and, trust me, I’ve tried), one can incorporate a few pieces into their wardrobe to honor this author and, perhaps, embrace a similar adventure mindset and way of living.

Quaker Marine Oysterman Hat

A well-documented favorite design for Ernest Hemingway, the long bill and vintage structure of this hat give it the look of something you’d find in your father’s woodshop. It’s perfect for duck hunting in Idaho (as Hemingway did) or leisurely casting a line in the river.

ISTO Ripstop Safari Jacket

Many photos capture Hemingway’s African adventures and big game hunting. While it’s no longer justifiable to kill elephants and other big game (if it ever was), it’s hard to deny he had some of his best outfits during these safaris. Portuguese brand ISTO’s Ripstop jacket has modernized this look and adds its own touch of refinement to an otherwise simple work garment.

Vollebak Nomad Sweater

One can find use for an oversized fisherman’s sweater in just about any situation, and Vollebak’s is top of the list for me. It’s a generous cut for layering or to roll up the sleeves and head outdoors to clear your head. Made of a combination of cashmere and lambswool, it’s insulating, fairly water-repellent, and breathable so it can last for years in the climates of Paris, Cuba, or anywhere in between.

El Casco Gold Cigar Cutter

Part of the appeal for a man like Hemingway was that he balanced ruggedness with a certain refinement and enjoyment of the nicer things. Hemingway was a cigar afficionado while living in Cuba and beyond. Having a cigar cutter like this one shows others you care about the finer things, but aren’t too prissy about it.

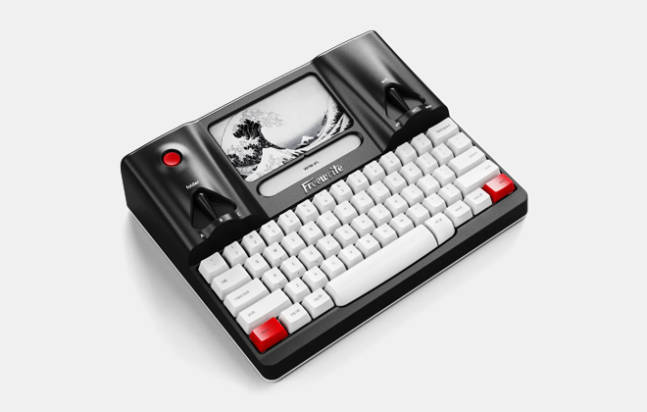

Freewrite Smart Typewriter

If you want to get into the writing mindset, Freewrite’s Smart Typewriter has much of the appeal of the vintage machine, but is designed for the modern user. It’s a distraction-free device that’s used for one purpose: writing. What’s nice is that it syncs to the cloud, letting you upload (and edit) on your computer after a long session at your desk.

Montegrappa Elmo 01 Fountain Pen

Hemingway’s time in Italy introduced him to Montegrappa, and its early model, the Elmo, was a favorite of his. A simple design with a light curvature to the barrel, it’s a great introductory pen for one looking to get into luxury pens. It may not make you write as well as Papa, but it doesn’t hurt to try.