We’re decently active readers here so we thought we’d compile and share a list of books we think every man should read at least once in his life. They’re not presented in any particular order, so feel free to jump around, but try to get to these before you die.

The Odyssey – Homer

Teachers like to think they’re introducing their students to Greek history with this book, but really what they’re giving them is one of the most violent, ridiculously unscholarly books ever written. People are bitten in half, smashed on rocks, lured to death by women things with sexy voices, do so many drugs they stop caring about existing, and have sex with goddesses. This isn’t history, it’s HBO in tunics. Link

The Lord of the Rings Trilogy – J.R.R. Tolkien

There’s a reason Middle Earth has stuck around as long as it has. Its history is almost as rich as our own real Earth’s, which is impressive, since it took billions of people to make ours and, like, two (mostly one) to make Middle-Earth’s. Tolkien’s linguistic expertise is the reason the books feel as rich as they do, seeing as how he invented one whole speakable language and pieces of half a dozen others. Instead of the cobbled-together feeling of lazy fantasy, Middle-Earth has rhyme and reason as its bedrock. Not only is the trilogy an amazing piece of writing, but by the end of your time with it, you’ll have a much greater appreciation for history, fiction or non. Link

Dubliners – James Joyce

Joyce is hard to get into if you don’t have the patient guidance of a tenured literature professor to lead you through the rough patches. Dubliners is on the list because it’s a great introduction to Joyce’s major themes and characters, plus reading it will make it that much easier to pick up Ulysses and/or Finnegans Wake, if they’d be something you’re into. Not that Dubliners is any slouching steppingstone. There’s some pretty heavy shit hiding behind the friendly Irish facade of early 20th century Dublin and Joyce isn’t afraid to explore it. Link

Jurassic Park – Michael Crichton

It’s surprising that a novel that relies on science as much at this one doesn’t show its age. Crichton knows his stuff, but one of his smarter moves is only giving as much sciency talk as we need to suspend disbelief. That way, we’re not distracted from the real substance of the story, the struggle between capability and culpability. Just because mankind can do something doesn’t mean mankind should do something. The book makes a pretty solid argument for ethical science, especially since not-ethical science means having your intestines pulled out by velociraptors. Link

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – Ken Kesey

Watching R.P. McMurphy antagonize his way through a mental hospital is as glorious as watching a train crash into a dying star. Everyone knows this won’t end well for anyone, but there it goes happening anyway. If there’s a moral here, it’s gotta be “buck the system, but don’t buck it too hard and know when to lay low. You can always come back for more later.” Which, knowing what we do about the 60s and how they turned out, sounds like a decent way to sum it all up. Link

The Road – Cormac McCarthy

If you can find a better father/son relationship in literature, tell us, because we haven’t seen one that beats the one between the Man and the Boy. They are the spine of the story, and everything that happens in the book is viewed through the lens of their relationship. Yeah, there’s a movie and yes, the movie is very good, but pick the book up. It’ll stick with you in a way the movie doesn’t. Link

1984 – George Orwell/Brave New World – Aldous Huxley

We put both of these in the same entry because everyone likes to talk about them as if they’re mutually exclusive, but we like to stay open-minded with our crushingly depressing alternate history global dystopias. Both make timeless observations about the public’s relationship with its government and itself and it’s easy to think of them happening in the same world in different cities. We would also suggest reading them as loose warnings and not explicit predictions. It gets a little bleak otherwise, and don’t think the world’s all that bad, no matter how hard it tries to convince us otherwise. Link Link

Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury

Fahrenheit 451 could be dismissed as the writings of a technophobe, but that wouldn’t be entirely correct. Bradbury saw the potential for abuse and placation present in television and, after seeing what’s become of popular programming and a good deal of the internet these days, it’s hard not to agree with him. We’re not saying it’s all bad, but maybe we could have listened a little better and been more discerning about what we made popular. We’ll keep it in mind going forward. Link

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater – Kurt Vonnegut

Slaughterhouse Five is excellent, don’t get us wrong, but God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater feels a bit more relevant these days. Centrally, it deals with a man who puts others above all else and the effect that has on different members of his family and community. Short version, they’re not happy and decide to do something about it. For us, all of Vonnegut hits hard, but the ending to this book hits hardest. Link

A Confederacy of Dunces – John Kennedy Toole

Ignatius Reilly is refreshing because he’s awful in so many ways. He’s unintelligent, cocky, fat, ugly, bullheaded, verbose, repressed, and mean and makes sure everyone knows it. You’ll find a thousand ways to hate him and everyone around him by the end. One of our favorite parts is when he gets his hot dog cart because he brings his signature awfulness to one of the best food delivery systems in the world. More than maybe any other book, Toole’s frustration with the world burns straight through this novel. This wasn’t a book written by a happy man. Link

Hard Times – Charles Dickens

Utilitarianism comes in different forms, though often not as obvious the one Dickens’ Mr. Gradgrind employs. While not Dickens’ most well-known work, it is the one that feels like it has the most to teach us in a time when economic hardship and ingrained old world prejudices keep people from exploring their potential. Dickens’ presentation of it makes it clear exactly who the victim of Utilitarianism is and it’s hard not to have even a small bit of personal reevaluation by the end. Link

The Complete Calvin and Hobbes – Bill Watterson

No one’s captured the free association and imagination of childhood quite the way Watterson has. It slams you with some serious, but healthy, nostalgia, regardless of whether or not you grew up in the same situation as Calvin. There’s also a serious case for Calvin and Hobbes being a collection of short stories instead of comic strips, what with continuity and storylines that run for multiple strips. If you haven’t read it at all or if it’s been a few years, pick up a copy. You’ll be surprised at how profound the comic can be in its simplicity and just how dated it isn’t. Link

The Plot Against America – Philip Roth

Roth’s novel explores an alternate history of the 1940s, one where FDR loses his reelection bid to the charismatic Charles Lindbergh and anti-semitic sentiment goes from whispers to official US policy. Roth’s he takes you step by step to the logical conclusion of a Lindbergh presidency and it’s a scary, highly relevant warning about the dangers of allowing prejudice to dictate who’s in public office. We’re not trying to push a political agenda here, but the similarities are too close to ignore, especially seeing how the 2016 election is shaping up. Link

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Series – Douglas Adams

The Hitchhiker’s Guide series reads like one giant novel rather than the series of five books it actually is, which is why we’re recommending all of them. There are a thousand vignettes scattered through the series, all of them filling out what becomes a galaxy brimming with life and bureaucracy and doing it in a way that completely meshes with what we’ve all suspected of the universe in the first place. That nothing really makes sense and it was never supposed to, so let’s all just do the best we can, shall we? Link

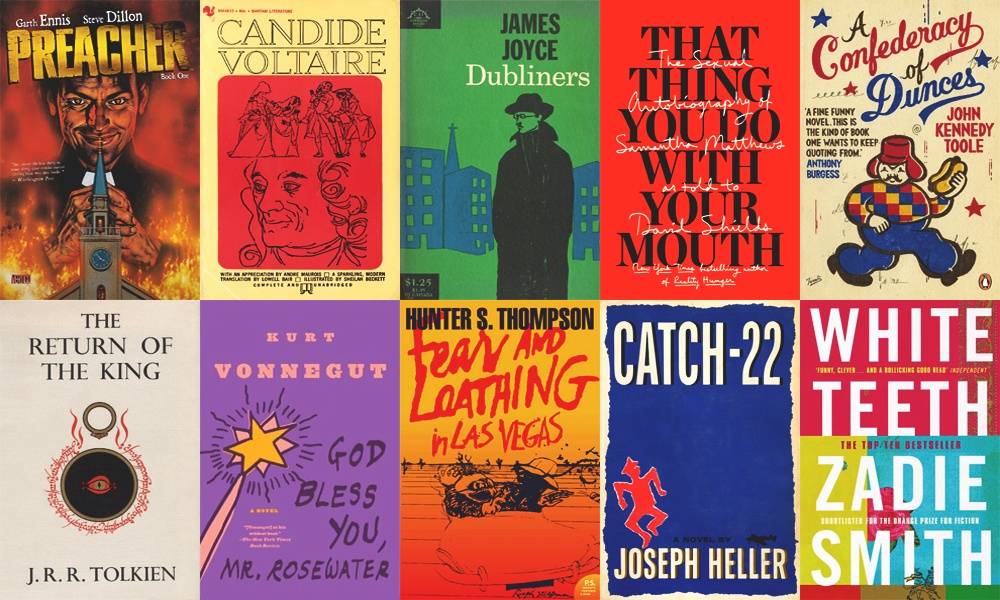

Preacher – Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon

Preacher is unapologetically what it is, and that’s a drug, sex, and violence fueled tear through the continental United States. There are Irish vampires, angels and demons, miracles, weird undead sex cults, Louisiana swamp people, and one hell of a twisted Saint. But somehow, none of that distracts from the central plotline, which is one man trying to do the right thing in a world that really, really doesn’t want him to. If anything, it enhances it, making Jesse Custer’s struggle all the more human, despite him having a god in him. Link

Catch-22 – Joseph Heller

“War is hell,” is the old adage we all know, but Catch-22 looks to modify that a bit. Instead, war becomes super goddamn weird. The book follows a bomber squadron in the Second World War whose collective sanity is slowly being eroded by whatever passes for power. Throughout it all, the main character keeps trying to prove himself insane enough to be kicked out of the Navy, which is precisely why he can’t be kicked out. Which is a catch 22 and yes, this is where the phrase comes from. It’s a great extrapolation of quirks and idiosyncrasies we see in day to day life, only this time, they’re affecting war. Link

All Quiet on the Western Front – Erich Maria Remarqu

Post-WW1 Europe was an increasingly disillusioned place and All Quiet on the Western Front was one of the first books to reflect that. Up until its publication, the generally accepted way to talk about war was as a gentlemanly pursuit not unlike polo, the theAtre, or other rich-people stuff. This book came around and was one of the first to openly admit that getting shot isn’t fun and that mustard gas can really put a damper on your weekend. Also, rats are terrible roommates, as are corpses. Link

Maus – Art Spiegelman

Maus is a hard book to forget once you’ve read it. It’s something of a saga, tracing Spiegelman’s father’s journey through both the invasion of Poland and the Holocaust. Spiegelman uses various animals to represent different groups, the Nazis as cats and the Jews as mice, making it a suspenseful game of literal cat and mouse. It’s absolutely one of the more poignant and emotional renditions of the Jewish struggle of the 1930s, 40s, and after, and the impact it had on survivors and their children. One of the few happy notes, the Americans are drawn as dogs. Link

Candide – Voltaire

Candide is an 18th-century French satire, in which Candide the optimist, student of the philosophy that he lives in the best of all possible worlds, travels all over the place and bad things happen to him the whole time. There’s death, assault, disease, confusion, kidnapping, and slavery, all based on real-world historical examples. The book doesn’t actually propose an alternate to optimism, so we have to assume it just doesn’t want people blinded by some cheap mantra like “best of all possible worlds.” Which, to be fair, is a decent lesson to take away and one that more people could benefit from. Link

Two Pints – Roddy Doyle

We’re convinced most guys’ ultimate goal is to be regulars at a local bar. Two Pints is the book version of that. It’s Roddy Doyle’s imagined transcriptions of the conversations of two Irishmen down at their local and takes you through most of the major developments of 2011-2012. It’s a short one and you could probably down two pints in the time it takes to read it. In fact, do exactly that. Make sure they’re imperial. Link

The Virginian – Owen Wister

We’ve had so many movies, books, comics, and TV shows, it’s easy to forget why the western genre was popular in the first place. But if you read The Virginian, you’ll see how the genre earned its popularity. It was the first of its kind and everything you’d expect from a western is present, from shootouts to love to matching wits with the villain. Despite being more than a hundred years old, the book remains exceptionally readable and compelling and reminds you that there’s no excuse for not being a gentleman. Link

Guards! Guards! – Terry Pratchett

The Discworld series of novels is hard to start and more than one person’s been intimidated right out of exploring. Consider this your introduction to the world, as Guards! Guards! is the first in the Night’s Watch series. You get a really solid starting point that gives you everything you need to know about the world, wrapped up in a funny, genuine, and unexpectedly exciting story. Link

Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal – Christopher Moore

You’d think it wasn’t possible to avoid blasphemy and sacrilege while writing a postmodern interpretation of the Gospels, but Moore does it. This book is both exceptionally funny while staying respectful of its source material. An argument would be made that this book actually enhances the Christian Messiah’s character, since we get to see him at every stage of his life, exhibiting an excellent understanding of the human condition. What’s more, Moore’s rendition of the crucifixion is so well-crafted and legitimately heart wrenching that we had to remind ourselves this was a story we’d heard before. Link

That Thing You Do With Your Mouth – Samantha Matthews and David Shields

It’s difficult to be as open about yourself as Matthews is in this book, but we should all be thankful she was. It serves as an extended monologue, so basically Matthews talking, which is where the title comes from, about her sexual past, a past that wasn’t the fairytale most people hope for. There’s a lot to learn from what she has to say, and it’s never hurt to get some different points of view. And believe us, this is a different point of view. Link

No Matter the Wreckage – Sarah Kay

Sarah Kay’s second collection of poetry is something special. We could make the excuse that her poetry reads more like fiction or that she’s using particularly traditional poetry, but the real reason she’s on this list is that she’s just good. She constructs some of the most relatable and accessible poetry this side of postmodernism, while never sacrificing substance for style. What’s more, Kay makes a genuine to connect with her reader, something that it seems a lot of other poets gave up a long time ago. Link

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas – Hunter S. Thompson

“We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold.” So begins Hunter S. Thompson’s most famous work of gonzo journalism. Based on two trips the good doctor took with his attorney to Sin City, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas blends fact and fiction into one hazy tale. You can get a contact high just from reading it. Link

My Struggle (Series) – Karl Ove Kausgård

To the uninitiated, Karl Ove Kausgård’s 6-book series can seem like a joke. We mean, okay, here’s a guy who’s led, for the most part, a pretty normal life. There were troubles, yes, but none that would make you take pause and feel incredibly sorry for him. And yet, he went ahead and wrote close to 4,000 pages on that fairly standard life. Then you read it. Drawing comparisons to Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, Kausgård’s books highlight the mundane, the relatable, and the business of being a human. It’s brilliant, and it will make you want a cigarette. Link

The Great Gatsby – F. Scott Fitzgerald

This is one of the few that forced school summer reading gets right, so if you skipped it in school, find yourself a copy now. It’s not a long read, if that makes a difference to you, but man is it dense. At the surface, it’s an interesting story about a guy’s cool but manipulative neighbor. Further down, it has something to say about almost every single human vice. Reading it, The Great Depression seems completely unavoidable. Past that though, since we have this book, we probably should have known better. Link

The Catcher in the Rye – J.D. Salinger

The Catcher in the Rye is one of those books that should be read once every ten years, at least, thanks to the changing way the reader views the main character, Holden Caulfield. When you read it at 14, Caulfield is a visionary and one of the only characters to truly understand what you’re going through. At 24, he’s a stupid, whiny kid who then makes you angry at the stupid whiny kid you used to be. At 34, you hope that you never have kids like him, and at 44 you’re just happy your eyesight is still good enough to read this without glasses. Link

The Sun Also Rises – Ernest Hemingway

Trying to select one Hemingway book for this list is like Hemingway trying to select one drink from the bar—they’re all too damn good. We’ll just roll with our favorite: The Sun Also Rises. The novel, which was published in 1926, tells the tale of a group of expats on their way to Pamplona by way of Paris. Much like A Moveable Feast, one of the real highlights is Hemingway’s ability to tantalize you with cafe culture and conversation that happens over shared drinks. Link

The Things They Carried – Tim O’Brien

Tim O’Brien’s collection of short stories focuses on the men involved in the Vietnam War rather than the political division of the American homefront. There’s a deep sense of tragedy about the book that O’Brien pushes one step further by making the reader constantly question how much of the book is true and whether or not it even matters. If these aren’t true events, are they still tragic? Or does the tragedy become true through the reader’s emotional response? It’s a great tool for dispelling some of the more venomous myths about the Vietnam War while also humanizing the guys who were sent over. Link

Naked Pictures of Famous People – Jon Stewart

Jon Stewart’s time on The Daily Show was so influential and powerful it’s easy to forget he pursued things outside of TV. He was in a few movies, did a lot of standup, and wrote things that weren’t TV scripts. One of those things was Naked Pictures of Famous People. It includes short stories, essays, scripts, and lists that show off a ton of talent, not just the political satire he’s known for. Link

My Documents – Alejandro Zambra, translated by Megan McDowell

International authors aren’t talked about a lot in the broad American audience, but Zambra’s work makes a compelling argument for seeking out translated work. My Documents is a book of short stories, written originally in Spanish and translated flawlessly by McDowell, and allows American readers to explore the similarities and differences, both more subtle than you’d think, between life in the US and Chile. While reading, you often have to remind yourself that the stories are taking place in South America and not the more residential sections of New York City or the like. Link

To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

Harper Lee’s most famous book is often people’s first introduction to race relations, criminal justice (or lack thereof), and the neighborhood weird guy. It may also be a slight indictment of modern America that most of the specific problems the characters face are still present today, especially since the story is set in the 30s, was published in 1960, and feels like it could have been written yesterday. It’s unlikely that you haven’t read it, seeing as how it’s one of the most widely-read books in the country, but if you haven’t, it’s not too late to catch up. Link

The Táin – Translation by Ciaran Carson

Seamus Heaney, a name you’ll recognize from your favorite version of Beowulf, loved this translation of The Táin, the ancient Irish epic, so that alone should be enough for you to pick up a copy. If you need more, the text starts with an Irish king and queen bragging about their kingdoms post-coitus and when they find out one has a better bull than the other, they start a land war which is repelled by a single 17-year-old and his charioteer. So it gets weird. It also shows that ancient poets might not have taken themselves as seriously as we thought. They were entertainers, after all. Link

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao – Junot Díaz

One of the reasons The Wire is often considered the greatest television show of all time is the fact that the dialogue feels authentic. It’s an incredibly difficult thing for a writer to master. Junot Díaz conducts a clinic on it in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. Set in Paterson, New Jersey, the story centers on the struggles of a nerdy, overweight Dominican boy as he grows up in Jersey. The story is narrated by a character named Yunior, who—and this is where Díaz shines—speaks in an eloquent yet street-wise manner. Slang can often feel fake and dated if the author is not plugged into the culture, but Díaz proves that, when done right, it adds a level of believability that can make a story soar. Link

The Corrections – Jonathan Franzen

Few novels capture the anxiety and despair of what many would call a fairly standard life like The Corrections. In it, Jonathan Franzen paints the picture of a family that, while not exactly the same as yours, feels recognizable enough. Then, through the actions of each of the Lamberts, he takes a microscope to the fears and troubles that reside deep inside you. The Lambert children are trying to make it on their own in East Coast cities far from their parents, but each encounters issues either financially or in their relationships. Back home things aren’t much better. It’s the pre-9/11 anxiety book that nailed it better than many post-9/11 anxiety books. Link

Walden – Henry David Thoreau

We didn’t want to include too many nonfiction works on this list, but Walden is such a fitting selection for a Cool Material list that we couldn’t leave it off. There has been renewed interest in Henry David Thoreau’s classic, thanks to the rise of the modern-day outdoorsman. Walden is a meditation on life, simplicity, and growth. It documents the slightly-more-than two years Thoreau spent secluded in a cabin by Walden Pond. During that time he connects with nature, ponders the direction civilization is going, and lives a life like a hermit. Even if you only have a good-looking axe on display, the book is thought-provoking and inspiring, perhaps even more now than when it was originally published. Link

A Good Man Is Hard to Find – Flannery O’Connor

Flannery O’Connor might have the finest throne in the pantheon of great short story writers, and the work that best explains why is A Good Man Is Hard to Find. Obviously it includes the legendary story of the same name, but it also includes nine other stories just as good. A theme of spirituality ties all the tales together, as many of the main characters question their beliefs when confronted with horror and abrupt change. In each of the flawed characters you can find a little bit of yourself, and O’Connor was beyond skilled at driving that home. Link

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay – Michael Chabon

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay is a sprawling historical novel packed with heavy topics—the plight of being Jewish in certain parts of pre-WWII Europe, the struggles of being gay in America at the same time, big business swindling. What makes it so brilliant, so enjoyable to read, however, is the air of levity Michael Chabon applies. It’s done, in part, by the childlike innocence of the main characters and also by the fact that it’s a story about superheroes, comic books, and the age of wonder. Link

East of Eden – John Steinbeck

Steinbeck is probably best known for The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men, both of which were strong contenders for this list. In our opinion, however, East of Eden is his finest work. In fact, Steinbeck would probably agree. Upon completion of the 690-page tome, he wrote to a friend, “This is ‘the book.’ If it is not good I have fooled myself all the time. I don’t mean I will stop but this is a definite milestone and I feel released. Having done this I can do anything I want. Always I had this book waiting to be written.” Link

White Teeth – Zadie Smith

Books like White Teeth don’t come around often. First of all, it deftly handles complex themes like race and immigration. The feelings, emotions, and challenges the characters face in relation to these things feel real, powerful, and, at times, excruciatingly brutal. Second, while it’s moving for that reason, it’s also a joy to read. Zadie Smith’s writing is stunning and witty. There is a bit of humor throughout, a bit of fun that makes the sorrow cut even deeper. By using multiple viewpoints, Smith not only displays her skills for fleshing out characters, but also gives you, the reader, different vantage points on assimilation. It’s the rare ambitious novel that really works. Link

Crime and Punishment – Fyodor Dostoyevsky

We had to give you one Russian tome to sink your teeth into. And by “sink your teeth into” we mean spend countless hours creating a chart of character names to remember and struggling with relationships. Instead of War and Peace, allow yourself the journey into Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky’s tale of moral struggles. The story, which was originally published in 1866, is about Rodion Raskolnikov (you’ll want that name on your chart), a man who decides to kill a seedy person and make off with their loot. He justifies this by saying he’s taking out a bad person and doing good with his money. A win-win, right? Like most Russian works of the time, it resonates on a philosophical level while still being an example of great storytelling. Link

Between the World and Me – Ta-Nehisi Coates

On occasion, a book will come along at just the right time to dissect the climate we live in. It will put into words—beautiful, eloquent words—the thoughts floating around in many of our heads. These books often go down in history as seminal works. Perhaps there is no greater recent example than Between the World and Me. Penned by The Atlantic writer Ta-Nehisi Coates as a series of letters to his son, the book deals with race relations in America today. As a black man, Coates shares some painful truths, emotionally-moving fears, and even some hope with his son. Simply put, it’s important you read it. Link

Infinite Jest – David Foster Wallace

Here are a list of things you may find less difficult than reading Infinite Jest: solving a Rubik’s Cube, beating Joey Chestnut in an eating contest, The New York Times Saturday crossword puzzle, teleportation. Yes, Infinite Jest can be challenging, at time laborious, and often confounding, but there is beauty in all of this. In fact, the “postmodern encyclopedic novel,” as it has been described, is best consumed as a meditation on such things as addiction, mental illness, depression, family, and much more. The story(s) take place in a dystopian future, where the United States, Canada, and Mexico have joined one large North American nation. Each year is sponsored by a specific corporation, resulting in things like the Year of the Tucks Medicated Pad and the Year of the Whopper. There’s tennis. Lots of tennis. Like we said, it’s weird, it’s confusing, but it’s also brilliant. Link

Pastoralia – George Saunders

There are few short story writers working today more revered than George Saunders. He builds stories around down-and-out characters who find themselves in ludicrous scenarios. But the true brilliance of Saunders is the way he uses these stories as a means to comment on contemporary life. It’s satire, yes, but it feels unique and distinctly Saunders. It’s like he sucks the emotion off the page and allows you to insert it yourself. In Pastoralia, his collection released in 2000, he gave us six stories that all originally saw publication in The New Yorker. Four of those six stories won an O. Henry Award, which is given to stellar short stories. It’s the ideal place to start on your wonderfully weird and poignant George Saunders journey. Link

Dune – Frank Herbert

So you want to get into sci-fi but don’t know where to start. How about with one of the best-selling sci-fi books of all time that also happens to be extremely approachable? Dune, the first book in the Dune saga, by Frank Herbert is a futuristic tale of planetary ownership and warfare. You know, standard sci-fi stuff. But where it departs from the heavy, techy sci-fi you might be envisioning is in how Herbert removes those stereotypical robots, computers, and other elements to simply tell a political tale that resonates on a very real level. Link

2666 – Roberto Bolaño

Roberto Bolaño’s final novel is not for the impatient. At over 900 pages, it isn’t exactly a beach read. What 2666 is, however, is Bolaño’s magnum opus, a final work that adheres to only the writer’s rules. Yeah, it gets a bit wild and surreal. At its most basic, though, the novel, which Bolaño wrote during the final years of his life as his health declined, is about the murders of women in a city named Santa Teresa, based on the real-life city Ciudad Juárez. Broken down into five parts (Bolaño originally planned on releasing five separate books to provide more wealth for his offspring), the novel showcases Bolaño’s skills at creating the hostile atmosphere and anxiety of a place, much like he did in The Savage Detectives. The slang is smart, the unease painful, and the words a joy to consume. Link

A Visit from the Goon Squad – Jennifer Egan

Existing in a world somewhere between novel and short story collection, Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad is truly a unique work, though you probably could have guessed that upon hearing her two sources of inspiration for it: Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, and the HBO series The Sopranos. Though the stories feature a collection of main characters that appear, disappear, and then reappear again, each chapter/story has its own distinct feel, though almost involve some aspect of the music scene. What Egan accomplishes is something special—a “novel” that feels as free and loose and beautiful as a Woodstock jam session. Link

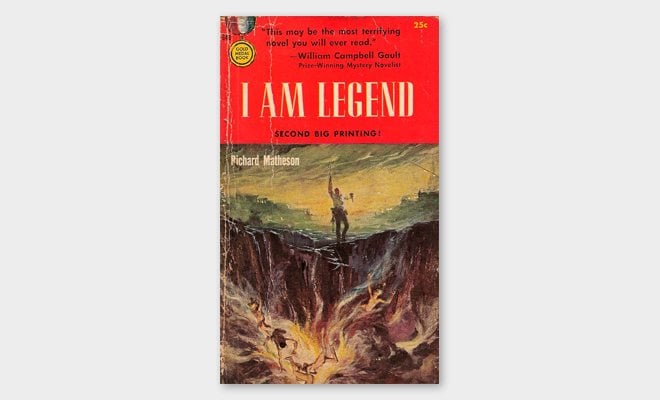

I am Legend – Richard Matheson

You almost definitely recognize the title from the 2007 Will Smith movie based loosely on the book. And we’ll emphasize loosely. Not that the movie wasn’t good (up to a point) in its own right, but the book gets much more into the philosophy of Robert Neville’s actions and convictions, the world feels more fleshed out, and the line between hero and villain isn’t so bold. Plus, in the book, the title makes way more sense. Though, we will give it to the movie in that Will Smith was a great choice for Neville and, if you’ve seen the movie, it’s hard to picture anyone else as you read the book. Link